In the Footsteps of Mary Tyler : B. Anuradha- Amita Sheereen

“Now I realize that there is more freedom inside the jail! No one is to worry about, no one to answer to.” Says Sunita Singh, from an upper caste well to do family, came in jail as her devrani (her brother-in-law’s wife) committed suicide, unable to bear suffocation of feudal middle class family. Her devrani’s family made her co-accused in her death. According to Sunita, her husband was a coward, always scared of his father. There was no pleasure in her domestic life. In her in-law’s family, there was no freedom at all. Everything was done with the permission of her father-in-law. No one can laugh, sing even in their own bedroom. She continues ‘there is no difference between home and jail…’

“Not only Sunita, most women here live in ‘freedom’,” sums up Bellapu Anuradha in her jail memoir –‘Prison Notes of a Women Activist.’ Anuradha was jailed in Hazaribagh central jail, Jharkhand for four years.

By the end of each chapter, my eyes were wet. I used to put book aside and started thinking about my days in Lucknow central jail. Although I was there for only 8 months and didn’t suffer as much as Anuradha did, but line after line it reminded me as if I was there only. It seemed she is narrating my own story.

Anuradha’s empathy with suffering women there is touching. She describes her own difficulties in jail almost nothing. Every time she tells a story, she becomes a part of it. Always helping, and consoling women in acute grief. Her revolutionary work continues there too. Whether she is dalit Durga of ‘Durga gang’ or Sonam of ‘Ek chadar maili si’. Or an adivasi women Sakun, whose crime was that once she went to jungle after cooking meal in a pot and a goat’s head stuck into it as there was not a proper door in her broken hut. Owner of goat complained in police and asked for compensation. She was unable to pay it as was too poor. In chapter Paro’s children, an old woman Paro, whose children were cats, she used to call them with names. She came in a murder case leaving her one daughter in home and brought one daughter with her in jail. After some years her daughter Munni was separated from her due to jail norms. Some missionary people took her and later Paro came to know with the help of Anuradha that she was sent to a shelter home in Deogarh after being raped. Paro was released after spending 16 years in the jail. There are Phoolmani, Reelmala, Shakun, shilpaand many more stories. Story after story one realises that there crime was only by-product of this unjust system. Most of the women in jail usually are from very poor background. Almost all are captive of cruel circumstances.

Like my own experience and others experiences, one’s heart cries out for children there. They are in jail for no crime they have done. Simply because they are sons or daughters of any prisoner landed in jail. Anuradha describes passionately how children in jail can see moonlight but not moon. Only animal they know is a cat which roam more freely there than humans. Anuradha very sensitively writes in her prison notebook that ‘freedom of a woman can be lost in several context’. Whether it is home or prison, women are prisoners of patriarchy, caste and class.

The only problem which I find in the book is that it doesn’t talk much about apathy of jail administration towards jail inmates. Rather, often it seems that they are too much supportive towards them. Whether it is matter of paro, or of children born or brought up there. My experience is that approach of jail administration and employees is quite opressive towards prisoners. They don’t have any sympathy towards them. They think prisoners are not worth treating like human being. Even under trials are also treated badly once they enter into the prison. All their human rights are snatched. Behaviour of jail emplyees is often objectionable. Their face and soul become like stones fixed in the ugly walls of the jail.

Perhaps it is because Anuradha has concentrated mainly on the stories of women suffering there. She wants to portray that each and every women is a product of patriarchy and society. She has committed alleged crime because of systematic circumstances that surround her.

B.Anuradha was arrested in October 2009 as a Maoist activist. She remained in jail for four years. Her father was a son of dalit labourer. He himself struggled and got education and a job. Anuradha was a bank employee and become activist and worked in women organisation and human rights organisation. She left her job and shifted to Jharkhand and started working in adivasi women in 2004. After coming in jail in 2009 she continued her work in jail also and become a darling of prison women. Both her hands always open to embrace women, longing for release, to meet dear ones, to get justice.

Anuradha gets excited when one day she came to know that Marty tyler had also been imprisoned in this same Hazaribagh jail. Suddenly the shadow of huge jackfruit treein the campus become deeper as it too saw Mary Tyler, the Naxal, trying to learn language, teaching children, caring women. Anuradha visits wards in which Mary was kept for five years. She tries hard once again to obtain book of Mary Tyler from her home and at last gets it after doing so many fasts to get book released from jail authorities. While in pursuit of footsteps of Mary Tyler, Anuradha finds that very little have been changed since Mary was caged here.

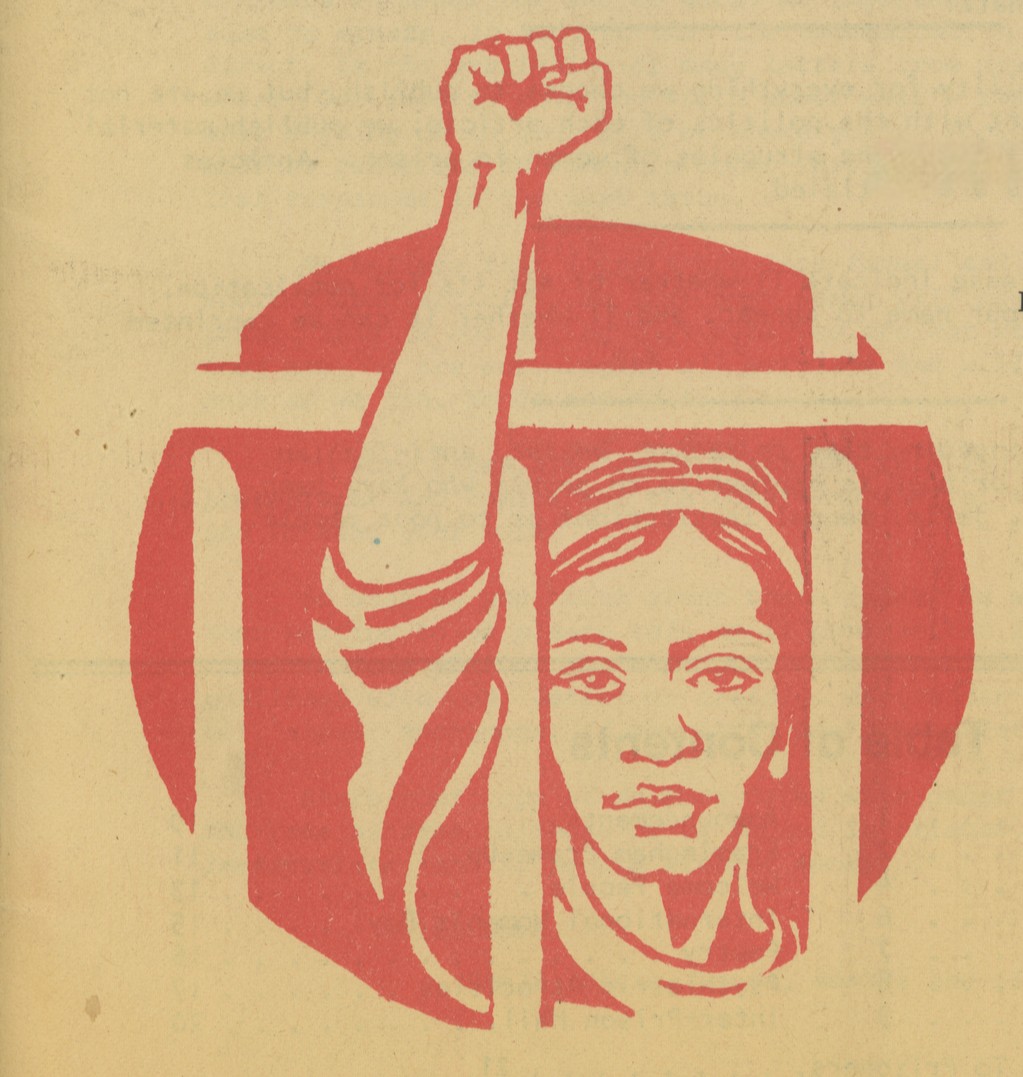

While going through Anuradha’s very passionate prison notebook feeling comes into mind that these revolutionary women are like pleasant soft, cold ointment on wounds of women suffering in the jail. Ironically, Like society, jail too need women like Anuradha. A very brave red salute to you Anu!